By Richard Sutcliffe

Indonesia continues to be amongst the world’s major exporters of coal, some 426Mt being traded in 2013 mostly to India and China. The potential problems associated with coals from Indonesia, highlighted in an article on this website by Peter Cook in 2010, are now well known to the shipping community and typically stem from a propensity of the material to self-heat, leading potentially to “spontaneous combustion”. Incidents continue to occur with barges of coal being presented for loading with stows that are evolving steam or even on fire.

Burgoynes has long been involved in providing advice on how such situations should be managed both by attending loading and discharge, and by advising remotely.

More recently, however, we have been involved in incidents where gas readings have shown that coal already loaded exhibits not only self-heating characteristics but also significant methane emission. It may be the case that such cargoes are commercially selected blends of different mined products because coals with these two properties are typically geologically different. The IMO International Maritime Solid Bulk Code entry for coal provides clear guidance as to how to deal with coals with either property but the guidance is less clear if both are apparent. Moreover, the basic strategy for dealing with self-heating is to starve the coal of oxygen (i.e. air) by sealing the hatch covers and other openings, whereas for methane emission the strategy is to provide ventilation – the exact opposite. Such incidents, therefore, call for very careful management and the need for expert advice.

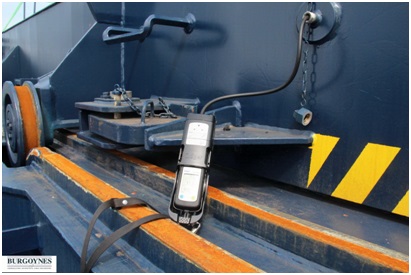

On board monitoring of coal cargoes in such situations relies to a very high degree on taking accurate gas readings, using equipment of the type specified in the IMSBC Code capable of measuring the concentrations of methane, oxygen and carbon monoxide. Although under “normal conditions” the Code indicates that one set of measurements per day is sufficient, if problems occur then in the initial stages this frequency might be considerably increased, perhaps to every two or three hours in order to monitor the conditions developing in the holds and the effectiveness of any actions taken.

The atmospheres that are sampled under such conditions may contain high concentrations of carbon monoxide and flammable gases (including methane) and virtually no oxygen. Experience shows that sensors repeatedly exposed to such extremes may eventually not provide accurate readings or may fail altogether, although modern sensors may be somewhat less prone to these effects. In addition, the readings obtained from different instruments at the same time are rarely identical and sometimes vary greatly. As an extreme example, in a recent case it was found that two different gas analysers, both within their calibration dates and both ostensibly working normally, on occasion gave readings from the same location that were an order of magnitude apart. Clearly this could have a major effect on decision making.

On the same topic, at the 94th session of the IMO’s Maritime Safety Committee in November 2014, a new SOLAS regulation was agreed (XI-1/7) requiring that on or after 01 July 2016 all vessels[1] must carry portable detectors capable of measuring the concentrations of oxygen, flammable gases, hydrogen sulphide and carbon monoxide along with the additional requirement that “suitable means shall be provided for the calibration of all such instruments”. It is hoped that by carrying calibration equipment, ship’s crews will be able more easily to identify when an analyser is not working correctly and needs to be serviced or replaced. Of course in many parts of the world technical facilities for the repair or replacement of analysers may not be immediately available. In the case of coal carriers loading in remote locations, Owners and Managers may thus wish to consider having two analysers on board both for comparison and back-up purposes.

When it comes to selecting suitable analysers, the IMSBC Code notes that the catalytic sensors used to measure methane concentrations (usually on the “%lel” scale) may not provide accurate results in atmospheres with a low oxygen content; “low” in this context typically being less than about 10%. This disadvantage can be overcome by the use of instruments that incorporate infrared (“IR”) sensors, which do not require the simultaneous presence of oxygen. In addition, modern analysers which can measure carbon monoxide concentrations of 2000ppm or more offer distinct advantages when monitoring incidents of self-heating.

For further details, please contact:

UK:

Singapore:

Hong Kong: